“All happy families resemble one another, each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

With these captivating words, the supreme Russian artist, Leo Tolstoy, opens his magnificent masterpiece, Anna Karenina, and grips at my heart from that first paragraph until the closing words, 963 pages later. It is impossible to express everything I felt and experienced and learned from inhaling every word of Anna Karenina and yet I remain pertinacious to attempt so, a month after its completion. During this time, I have tossed one book after another aside, not because I found them to be in poor taste, only because it has been impossible to reap pleasure from lesser purity, lesser prose, lesser richness, anything lesser than Anna K. Reading Tolstoy is falling in love – with reading, with words, with characters, with thoughts, with dialogues, and with Anna and Tolstoy both – and finishing Anna K is that first love’s broken heart, never again will a novel touch me this profoundly, move me this deeply, and ache me so much. At least, I am sorely convinced as such today.

In November of 2008, I randomly picked up Irina Reyn’s “What Happened to Anna K?”, a modern take on Tolstoy’s original creation in print. An anomaly of choice for me as I am not one for either sequels or adaptations of books into another author’s versions. Can we not let the original remain the end-all and be-all for that literary work?

But Reyn’s authentic Anna K. was an obsessive read for me. The author is extremely gifted and she will always be the one to have first introduced me to Anna, even if portrayed as a modern day 21st century Russian-American living in NYC! A month or so later, I picked up my hardcover Anna Karenina (Maude translation from Every Man’s library) but that was over a year ago. The book settled down on my shelf where I kept staring at it with intimidation.

One day I am going to read it, I would say. Doubt befriended procrastination and a year of waiting went by.

Now, I regret empowering either of those evils in my mind; reading Tolstoy is for anyone and everyone and the pleasure is immense for one spectrum of readers to another. In February, an angel of a friend promised to keep me company as we set out to read and finish Anna K together. Perhaps the only other thing that can add sweetness to reading Anna K. is to share the journey with a friend. In this post, I beg forgiveness for length as I pay tribute and gratitude to the world that Tolstoy weaved for us in his genius art.

Disclaimer: See Wikipedia entry for an excellent summary of the plot; I will not cover the plot in detail as that is not my point of this post. All of the writing here are based on my opinions and observations unless I state otherwise. I did not consult Wikipedia or other Tolstoy sources online. I organized my review as such for us:

Tolstoy on Writing Style:

The use of cohesive, comprehensive and exquisite prose:

No word feels redundant. No passage seems irrelevant. No character is without a purpose in the dozens upon dozens introduced. Not a word or paragraph would I wish to eliminate even among topics I found challenging to read. The best surprise of all on reading Anna K. was the ease of reading Tolstoy. I had prepared for a highly complex Russian novel; instead I found one to be of great depth, scale and detail and yet not lacking in simplicity and purity of language. The plot of this great novel resembles a tree with all the characters and situations echoing the staggering number of branches, each extending here and there, growing this way or that way, varying greatly in size and shape and form, some withstanding the wind while others snapping in parts but not a single branch falls from the foundation; likewise, not a single character or scene is less than essential to the whole of this novel. No, the exquisitely written Anna Karenina preserves unity in all its depth and breadth.

The use of humor:

Tolstoy takes the time to entertain us. Almost always, the humor is a sad irony on a twisted character’s view on life, usually Oblonsky attracting the most laughs followed by Levin, two of the prominent characters. The humor, entertaining and unique, is never without a purpose; in fact, we get to know Oblonsky mostly through his comical behavior and his bewilderment of the ordinary. The other passing characters such as the painter in Italy and Vronsky’s friends add delightful humor to the pages, all the while exposing the main characters in more depth to the reader. Other times, the humor takes the form of author’s opinion in narration, again stemming from the irony or pretense observed in manners and ways of the Russian elite society. This use of self-deprecating humor, as Tolstoy himself was a Count and lived among Russia’s highest social class, gives to us the author in all his sincerity and honesty.

The use of French language:

To my delight, Tolstoy incorporates frequent French dialogue, idioms and expressions in his character’s interactions throughout. I had not been privy to the extent of French culture and language influence among the Russian elite. I had been feeling slightly robbed for not reading Anna K. in Russian because there are no doubt meanings lost even in a translation that the author himself blessed (The Maude couple was a contemporary of Tolstoy and he had approved of this translation), following the French first-hand as written in Tolstoy’s own words was a small relief.

The use of Omniscient Point of View:

Tolstoy is a genius of a story teller. In the omniscient point of view, the author is know-all and tell-all and with his realism style of writing, depicting of people as they appear in everyday life, he shines an eternal light on his art. How smooth the transitions come about as Tolstoy switches his role of a narrator: from Dolly’s broken heart after her husband’s acts of infidelity to Kitty’s high hopes and subsequent misery at a dance ball, from Levin’s mad love for his land and his religious doubts to Vronsky’s self-love, eccentricities, and adoration for Anna, from Karenin’s anguish and meditations on revenge in reaction to Anna’s infidelity to Anna’s own fully exposed heart and soul with which the author indulges the reader. Tolstoy can occupy the mind of an old man equally as well as that of a young girl, and just as easily the thoughts of a mother, a child, a priest, a farmer, and even a dog (at one point, Levin’s dog becomes the narrator hunting for birds and observing life and people, all in a most realistic nature!).

With the timeless classics of our time, the lines between reality (what actually happened) and fiction (what happened only in one’s imagination) sometimes become blurry. With Anna K., there was no blurring for me; in fact, I felt quite convinced that Anna must have existed in more than just my mind; she seems ever more real and alive than most people I have met in person in my whole life. Ah the powers of genius men and women with pen!

Tolstoy on Depth of Knowledge:

Anna Karenina runs through many themes, every single one a topic to which we can easily relate some 135 years post publication of this classic. It would be a terrible mistake to categorize the novel as a book on marriage and infidelity alone. Tolstoy does not refrain from integrating a world of important topics, naturally topics important to him, in astute detail and in this regard, his knowledge of each subject matter is astounding. The novel shifts between the themes of family, marriage, infidelity, jealousy, Russian politics, the struggles between farmers and serfs and the role of land and patriotism, faith and religion, education of women, sports such as hunting and horse racing, Renaissance art and lifestyle, culture and the role of high society life in the character’s lives. Tolstoy not only covers each topic in astonishing prose and detail, he seamlessly adjusts the tone and perspective as he switches between each character and their particular view point on the topic at hand. A marvel through and through.

Tolstoy on Character Depiction:

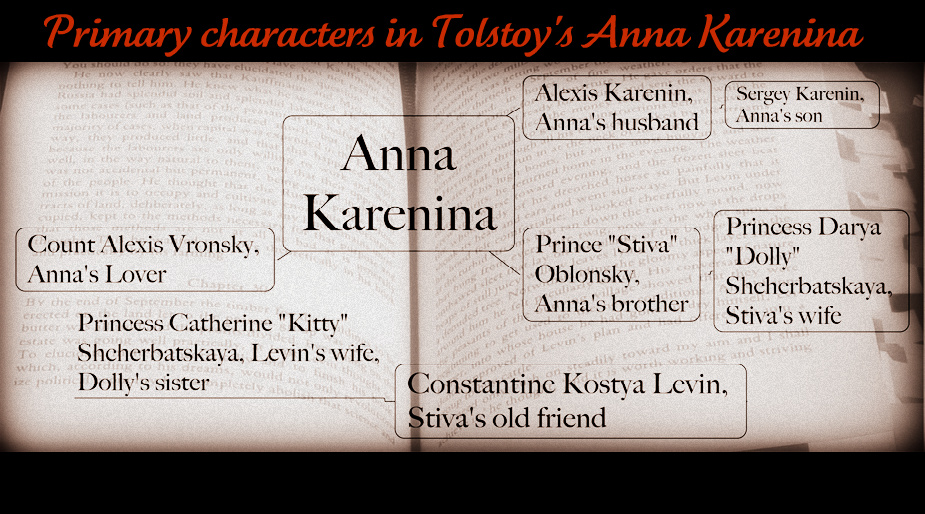

If I had not known the title of this book, would I have concluded Anna to be our protagonist? I wonder. She seems no more and perhaps even less central than Levin at times. Both of them occupy the main seat nearly as often followed closely by those surrounding them, Karenin (Anna’s husband), Vronsky (Anna’s lover), Kitty (Levin’s wife), Oblonsky (Anna’s brother) and Dolly (Oblonsky’s wife). Tolstoy is generous with his pen toward many characters; throughout the novel’s 8 parts, friends of friends, servants and nurses, counts and princes, distant characters and lengthy conversations, take us away again and again before bringing us home to Anna.

Perhaps Anna is indeed reflected through each of these characters and the society around her as my reading partner Rebekah observed below (paraphrased below) when I complained about lack of Anna’s overall “stage time” :

Yes, where is Anna!? With this author who writes an entire world, she is reflected in his world. The theme stated in that first sentence, The Family, means we’re watching poor Anna in contrast to how easy it is for Oblonsky to be unfaithful, the measure of Dolly’s happiness with her children, the unmarried characters’ emotional expectations (or not) of marriage and what personal resources they will or will not have when marriage can or cannot fulfill all their hopes for happiness, the exact nature of the society that is the terrain Anna and Vronsky meet in, must swim against, and will or will not fall heavily on them.

Tolstoy’s deep exploration into each character psyche aside, we do not even meet Anna right away! The novel opens with the unfaithful Oblonsky waking up to his own infidelity’s consequences, mustering up courage to meet the disappointments incurred to his wife Dolly, a matter which he finds quite surprising! We see how easy it is for Anna’s brother to be unfaithful and the socially accepted terms and forgiveness afforded to him even by his own wife, ironically, thanks partially to the advice of visiting sister, Anna. The twisted irony which follows is anything but humorous.

Tolstoy on Mother Nature:

It is impossible to dismiss Tolstoy’s devotion to nature in reading Anna K. When I watched the incredible film, “The Last Station”, the last year in the life of the author, this virtue was evident in all his actions. His vast descriptions of farming, nature, the woods, the rise and setting of the sun, are as breathtaking in prose as the nature itself he describes. It is possible that Levin represented a lot of Tolstoy himself, especially for two occasions which the novel repeats what Tolstoy himself had lived: Levin not having the right clean shirt before his wedding to Kitty and therefore being awfully late as well as a fun silent word-game Levin plays with his beloved Kitty to convey his thoughts without expressing them, all of which she guesses. Tolstoy is known to have done both of those in his own life. On a more serious note though, the prologue draws parallels between Levin and Tolstoy where politics and Russia’s land ownership philosophies are concerned, topics which I could appreciate as I read and waited with baited breath to reach Anna again in the story.

Tolstoy on Marriage and Infidelity:

It is not clear to know where Tolstoy stands on these delicate topics. We know from his biography that he was estranged from his wife at the very end of his life and that is all. On infidelity, he shows us Oblonsky’s quiet acceptance of his own actions and his wife’s suffering and forgiveness; their life together goes on nonetheless. Then we see Anna who commits the act and suffers miserably, desperately and hopelessly falls into despair, a fate neither her lover nor her husband come close to experiencing. Was Tolstoy showing us the blatant hypocrisy of society in treating a cheating married man versus a cheating married woman? Was he implying that it reflects his own thoughts toward infidelity as how it should be? I doubt the latter and therefore choose to believe the former. When my friend Rebekah, distraught at the fate of poor Anna, wished for a different ending, it was all I could do to think that it would simply not be the story it is. We human beings seem to crave tragedy even if we flood it with compassion and sympathy.

“Vengeance is mine; I will repay”. The epigraph to Anna Karenina comes from the bible (Roman 12:19, King James version) but the original meaning seems to be thwarted. It must have dozens of translations for Tolstoy never explains who is to take the vengeance and who repays for what she/he did. We can only extract our own meaning and I am choosing not to analyze it to death (I can hear cheering from all of you! ;)). Well, since Anna is the heart and soul of this masterpiece to me, it must be Anna. Indeed, toward the end, she seeks vengeance on Vronsky who could neither fulfill her anymore nor contain her paranoia and she does so by repaying with the biggest price of all, her precious life. In weaker parallels, Karenin at one point wanted to seek vengeance on Vronsky but did not carry it through and Lydia, Karenin’s companion, sought some vengeance on Anna by not granting her the divorce she so badly needed to gain her freedom.

Reading is the best pastime for an active mind! If you like to see the other book reviews, check the index of In Print.

Random Musings of the Heart about Anna Karenina:

In every page and passage of Anna Karenina, I strip through a rainbow of emotions and I do it again on the following page. There is either the amazement from descriptions which brought everything and everyone to life for me, the amusement from observations on culture, society and humanity, the enjoyment of brilliant dialogue and the movement from immense articulation of feeling and thought; there is the thrill of short-lived bliss preceding the compassion and sadness for those suffering from one of life’s harsh turns, or simply the sheer joys of reading a pure and timeless classic, Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina.

In every page and passage of Anna Karenina, I strip through a rainbow of emotions and I do it again on the following page. There is either the amazement from descriptions which brought everything and everyone to life for me, the amusement from observations on culture, society and humanity, the enjoyment of brilliant dialogue and the movement from immense articulation of feeling and thought; there is the thrill of short-lived bliss preceding the compassion and sadness for those suffering from one of life’s harsh turns, or simply the sheer joys of reading a pure and timeless classic, Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina.

Tolstoy was generous in a great many aspects with Anna K. but he left me starving in one. In an unforgettable essay by Simon Blackburn, he writes “Lust subverts propriety; it stole Anna Karenina from her husband and son and Vronsky from an honorable career.” Blackburn builds up this lust in his imagination and I suppose so should I because Tolstoy leaves all, and I mean all, to imagination where Anna and Vronsky’s affair is concerned. I regret so much not being able to know in Tolstoy’s words, Anna’s exact moment and nature of giving in to Vronsky and any or all subsequent moments of lust, pleasure, joy and sensual bliss. Alas, Tolstoy affords us no such details as I learned quickly when he jumps forward to a scene where the two are already together: “That which for nearly a year had been Vronsky’s role and exclusive desire, ….; that which for Anna had been an impossible, dreadful but all the more bewitching dream of happiness had come to pass.” (Chapter 11, pg 175). Subsequent scenes of Anna and Vronsky remain chaste and pure with so much implied, leaving me wanting more of Tolstoy in this one regard.

In Madame Bovary, one of my favorite classics, Emma is selfish, conniving, exploratory, soul-searching and always putting her own pleasures forth before those of her lovers or anyone else in her world. No matter, I still loved Madame Bovary for her bold, courageous, and undaunted pursuit of her heart’s many desires but alas, she is nothing like Anna K.

Our Anna is love and compassion, sadness and confusion all in one. She has been so deprived of love and affection in her marriage that she is near starvation when she finds herself in Vronsky’s arms. She is both the sinner and the victim in her own affair. She is all beauty and allure, with a softness that melts every heart and an aura about her that captivates all who come in her contact. She is a mother in love with her son (but not her daughter from Vronsky) and unable to choose between him and her lover. She is a fawn in desperate need of love, a fallen woman whose guilt consumes and confuses her to utter despair and hopelessness. She lives a short burst of happiness, sadness, love, bliss, confusion, grief, vengeance and most of all, a tragedy.

She is Tolstoy’s most unforgettable figment of imagination and will live indefinitely in my heart.

I am Farnoosh, the founder of Prolific Living. So glad you are here. My mission is to empower you to unblock your creative genius to live your dream life.

I am Farnoosh, the founder of Prolific Living. So glad you are here. My mission is to empower you to unblock your creative genius to live your dream life.