In “What happened to Anna K.?“, Irina Reyn gives us the life of Anna Karenina in a new light. Reyn’s writing and story-telling was simply riveting. This brilliant young author had me captivated and glued to her book from page one. Reyn’s writing style is remarkable for such a new novelist. Her spellbinding way of telling the story of Anna in modern day New York takes you through a much changed setting from Tolstoy’s Russia backdrop in late 19th century.

To my own regret, I have not yet read Leo Tolstoy’s “Anna Karenina“. My only preview to Anna’s character before this book came from my absolute favorite essay, poignantly written by Simon Blackburn titled “In Defence of Lust“: “Lust subverts propriety.“, Blackburn writes, “It stole Anna Karenina from her husband and son….” Was lust really the culprit that stole our Anna?

Oh the gripping story of the sexy, the sophisticated, the elegant Anna. The longings and yearnings of Anna for so much: for lost opportunities, for passage of time and her fading youth and beauty, for her home in Russia, for her Mr. Darcy, her Heathcliff or her Romeo in her life. Irina pointedly describes these longings. These are the essential elements that make up the complex Anna K. Never has my own longing for the years gone by and fear of the few remaining ones in fleet been better articulated. I loved Anna at once because I could immediately identify with her on all levels.

Of all her yearnings, Anna K’s longest struggle is with time, that voice that beckons us to hurry and slow down at the same time, and never lets up, no matter what blow we suffer in this world and what tragedies befall us. It ticks away indefinitely. I can relate acutely to Anna’s emotions with time, as Reyn writes “Her relationship with time, once so affectionate, lovingly doled out on the abacus, was now openly hostile. How could there be no going back? Anna thought.” (pg.167) In this context, we see Anna’s constant agony in dealing with the reality of our finite time on this earth. This subtle quiet passing of the weeks, months, and years – and the older we get, the more distinctly we remember our childhood and more tightly we long to revive and relive our youth. It is the trick we play with ourselves by thinking that 35 is really awfully young when we pass the mark whereas the same age seemed awfully old when our parents reached it – not a place we could see ourselves anytime soon. However did we get here so fast? Perhaps it is only by living well and fully that we can find solace in the journey and the unbelievably quick pace on which it insists. Through a rich, honest, healthy, and determined life, I know we can uncover the mystery games that time plays with our minds and get closer to understanding the significance of our time here on this earth.

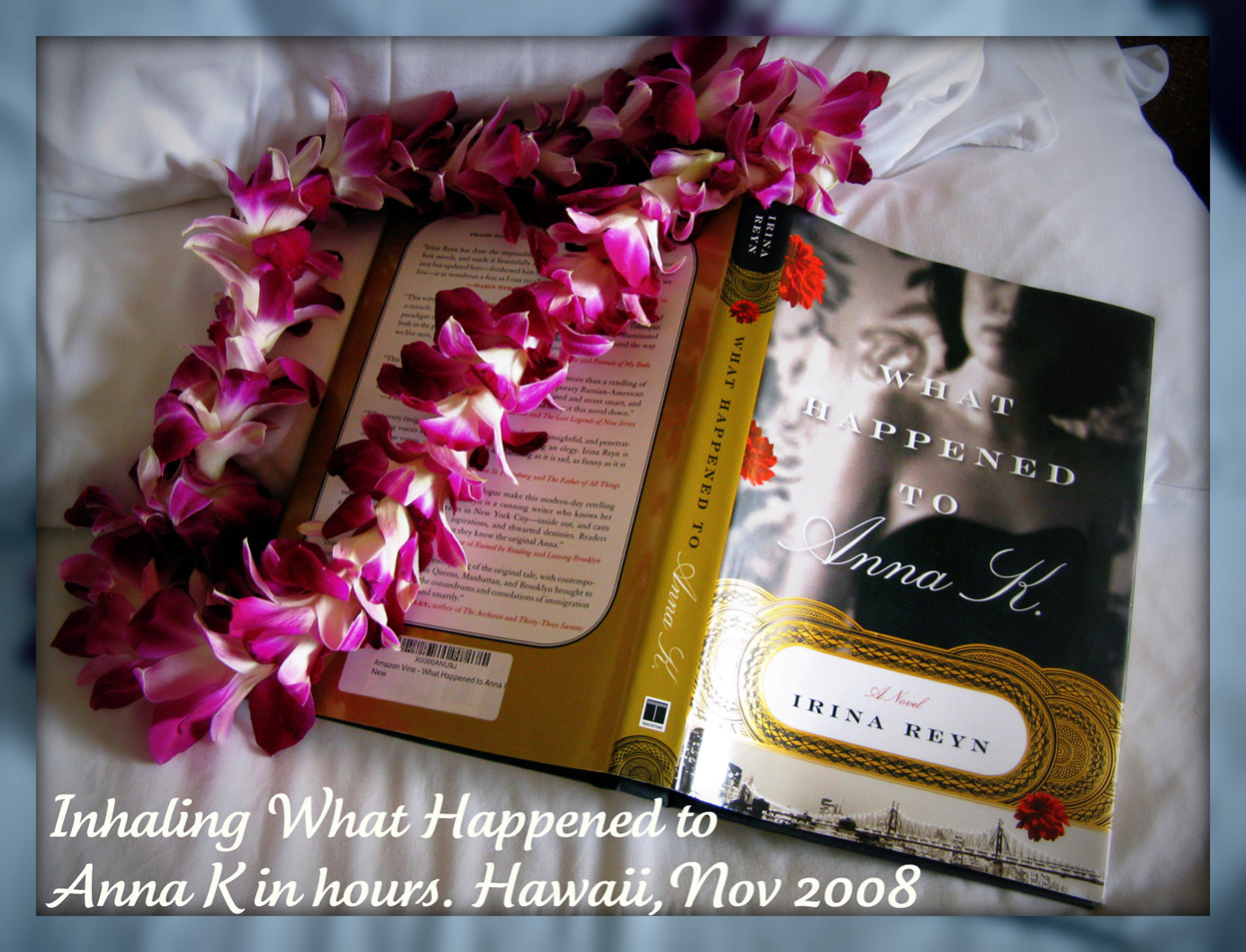

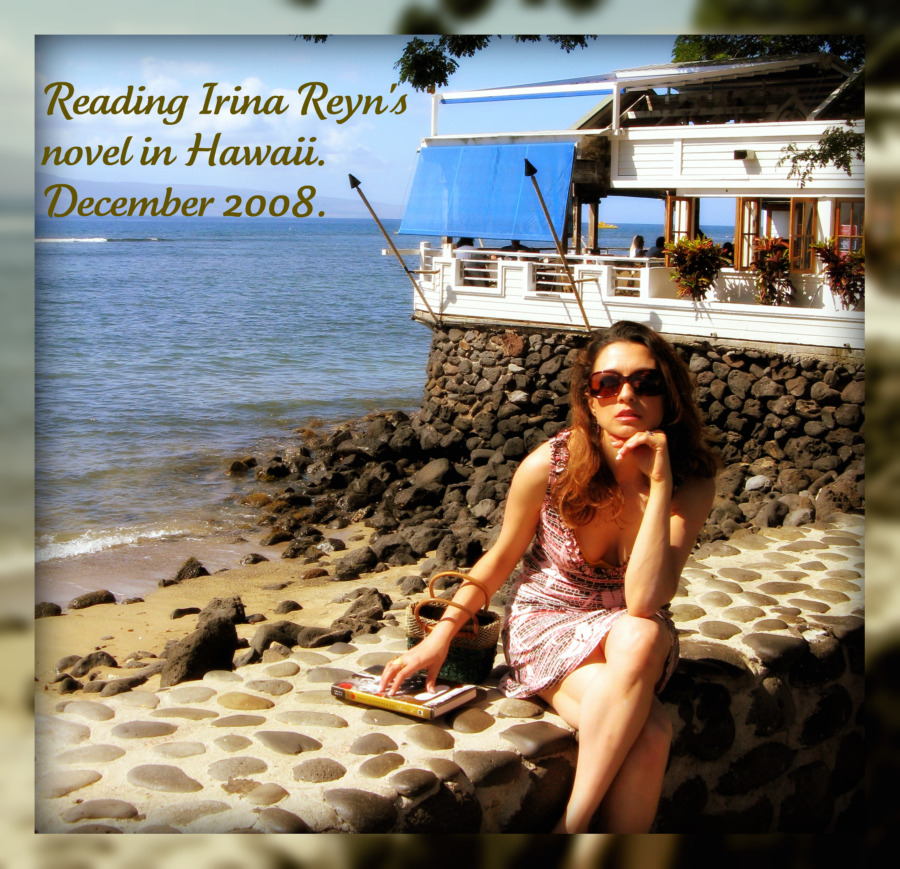

Reading is the best pastime for an active mind! If you like to see the other book reviews, check the index of In Print.

Anna Karenina blends her fiction with her reality like the ingredients of a recipe that belong together. At the age of 37 and still unmarried, her Russian parents have no more excuses and only shame to carry to the social parties and traditional gatherings of their upscale Queens lifestyle about their unwed daughter. The social and cultural pressures of Tolstoy’s 19th century for women do not seem that far-fetched when placed in modern day New York city’s Russian quarters even in 2004.

Anna fights the social and cultural pressures poorly. She fights internally, and submits on the outside. She marries Alex, and for terrible reasons to boot. His financial security would make many women happy, and while Anna’s taste is not inexpensive, her needs lie elsewhere. Anna plays more a silent observer than an active participant to her own life, taking in the shocks of what happens to her from a distance — she is married, she has a son, she is 39, she has gained weight during the pregnancy and her body is not the same after her son’s birth — she observes herself from a distance and mourns every event, as it is all one loss after another in her eyes.

She is one of the most well-read women of her time. She has read voraciously since a very young age, and is obsessed with the heroines of her stories. She imagines it was she who played up against her Mr. Darcy, and Heathcliff, and countless others. She longs for a man who worships her, and would someday write a novel about her. The notion of being worshiped and written about plays a central theme in Anna’s existence. It is not so much about finding love as it is about love finding her and playing out just like her favorite novels. She will be present to receive it. She knows every line. Love and time need not concern themselves with such trivial matters. If they would just present her dreams to her, she will be off on her way.

With all due respect to Blackburn, lust did not steal Anna away from her husband and son. Lust played a minor role at best. It was the obsession with the fantasy of being a heroine in a novel, revered for her beauty and mystique that consumed Anna and attracted her to David. Alex was too practical, too predictable and real. David was the epitome of American freedom, dream and beauty. The mundane affairs of daily life, even in the posh living style of Upper East Side, held no interest for Anna. She lived and breathed her novels and idolized a hazy vision of happiness in her mind.

Katia Zavurov is Anna’s younger cousin and looks up to her fervently. Lev Gavrilov has cared about two things all his life — French movies and Katia, or “Vasilisa the Beautiful”, the name he has given her. I am baffled by the nature of Lev and Katia’s relationship leading up to and during their marriage, which in itself comes about strangely even for Lev. How can Lev’s deep emotions for her go unexpressed when all he was waiting for was a window of time and a chance? Katia is the sweet and obedient Russian girl — always doing what is expected of her, and shoving aside doubts when they arise. She marries Lev because she feels unwanted by any other suitors and her clock is ticking. Their faith is a strange irony. She is oblivious to his worship and love for her, and he makes no attempts to tell her. They go on living as such, Katia feeling desperately inadequate as a wife and Lev, always rushing out to escape his reality at the French movies.

Anna steals David away from Katia. She feels bad, she really does — yet nothing will interfere with what Anna Karenina wants in life. Katia be damned, they all be damned, Anna reaffirms her own actions.

The slow onset of attraction, which does not materialize further, between Lev and Anna, happens at the very end. Reyn develops her two complex characters, Lev and Anna, all the while in parallel and separately. Anna by now has built imaginary doubts about David’s love and devotion and feels ever so alienated by her world. Lev, in utter loneliness for not communicating with his own Vasilisa, feels disgust and lust towards Anna. They have a brief encounter towards the very end of Anna’s story. That is the end of Anna Karenina’s story. Why does there have to be an end to every story?

For all her beauty and grace, Anna feels unloved and insecure. She is wanted and envied by all, and yet she feels threatened in her love affair to David. David who knows Anna is the only woman for her. The unexpressed thoughts, the unspoken words, they steal Anna away from us as much as her own illusions about life and happiness.

I am Farnoosh, the founder of Prolific Living. So glad you are here. My mission is to empower you to unblock your creative genius to live your dream life.

I am Farnoosh, the founder of Prolific Living. So glad you are here. My mission is to empower you to unblock your creative genius to live your dream life.