It is best to be reading Wuthering Heights in the cold of winter. Perhaps when and where we read our classics and our favorite novels makes them particularly memorable to us years from now. I read Emily Bronte’s brilliant singular novel this winter, a few days short of Christmas. I already knew the story, all the main characters, and had watched the movie. Yet the reading of the book was every bit as tantalizing as reading the world’s greatest novel. Even in my exciting and thrilling life, every cold evening, I would psyche myself to the excitement awaiting me as soon as I scurry under my covers. I would exclaim loudly, to no one in particular, “Goodnight – I am going to bed with Heathcliff”!

When you are reading a good thriller, the suspense and the unknown moves you forward as you turn the pages to move with the story. Any spoiler could easily have you cast aside the book. Is that why thrillers do not age gracefully into classics? Knowing the ending of a classical novel, or even the beginning and the middle for that matter, has no effect on whether we read it or not. It is the writing that we crave through and through. It is the particular way Jane Austen articulates the depth of thoughts distressing Elizabeth Bennett even as we know well her present distress and her unfolding situation. It is the unforgettable manner in which Victor Hugo paints Jean val Jean’s character in our imagination: vividly, distinctly, and slowly. It is not the newsworthiness or the sea of knowledge and information which draws us to read a classic. It is the unmistakably unique style in which a genius writes and gives the world a gift in the process. It is timeless writing for timeless audiences. It cannot be justly reproduced in a movie, described in a review, or summarized in the world’s lengthiest conversation. And it is without a doubt Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights.

Wuthering Heights is not just any great classic. There is a bittersweet aftertaste to the words, phrases, and descriptions of Bronte’s characters and the magical moors. It is a disservice to yourself to read this story without pause and process. Bronte has not just written a magnificent novel; she has written a novel that resonates with the beats of the heart like the sounds of a well-orchestrated symphony. Her prose echoes like music in the ears, her words hang in the air with a quiet vibration, her authenticity is worthy of one thousand literary awards, her descriptive delivery of every emotion- grief, pain, regret, agony, bliss, pity, joy, sorrow, loneliness, longing, anger, passion – sublimely accurate, and her capacity to capture the essence of human love, loss and life is simply and unarguably perfect. Brontë achieves this, all of this, in her first and only novel, a masterpiece for all eternity to know and behold.

Catherine Earnshaw and Heathcliff crave, ache and long for one another fiercely, savagely, and with an intensity that is too raw even for lovers to recognize instantly as love. In fact, it is hardly appropriate to characterize the nature of their feelings as love – at least, not beyond the initial brief period which they enjoyed together in their youth. Even that love is worthy of being called something else – something only Catherine can feel and express, as she does to Nelly in her most vulnerable state:

“My greatest thought in living is Heathcliff. If all else perished , and HE remained, I should still continue to be….Nelly, I AM Heathcliff! He’s always, always in my mind:not as a pleasure…but as my own being.”

Reading is the best pastime for an active mind! If you like to see the other book reviews, check the index of In Print.

The story of Catherine and Heathcliff is not just tinged with sorrow – it is lacking gravely in all moments of bliss that are stolen from the star-crossed couple. It is a brooding tale of a strange love that unfolds with agony, as Catherine and Heathcliff are torn apart by circumstance. Catherine marries Edgar, and Heathcliff runs away for 3 years. It is needless to state that circumstance and years not only intensify their fierce passion, they turn Heathcliff into a vengeful soul and Catherine into a lost one. Even on Catherine’s deathbed, even as she is about to depart Heathcliff’s world, neither of them is calm and forgiving and savoring these last moments. Can love rip our heart out and turn us into a savage beast, even toward that which we loved with all our might? Heathcliff, on the verge of all madness moments before Catherine dies in his arms, is overcome with anger more so than grief:

“You teach me now how cruel you’ve been – cruel and false. Why did you despise me? Why did you betray your own heart, Cathy? I have not one word of comfort. You deserve this. You have killed yourself. Yes, you may kiss me and cry and wring out my kisses and tears: they’ll blight you – they’ll damn you. You loved me – then what right had you to leave me? What right – answer me – for the poor fancy you felt for Linton? Because misery, and degradation, and death, and nothing that God or Satan could inflict would have parted us, you, of your own will, did it.”

Perhaps, from one perspective the Yorkshire moors and Nelly are the two constants in this story – unchanging from year to year, season to season – and adapting to nature and age gracefully and without resistance. Nelly who is there all along, the housekeeper, the nanny, the nurse, the storyteller, and the one present mind and adaptable soul, she is more in harmony with the moors than Catherine or Heathcliff. The moors play a significant part in this story. In general translations of Wuthering Heights, they have come to embody the wild natured love between Catherine and Heathcliff. I see it differently. While Heathcliff and Catherine each breathe and belong with the moors, they seem more at odds than at harmony with it. If the moors were alive and if the moors could speak, they would tell of a love that moves with mother nature, and with the rhythms of one’s own heart and soul. They would tell of a love that lives and breathes the seasons in complete sync with one’s lover, and cares not for the material world, the opinions of society, or the plans for the future – only the present and the command of one’s heart to conquer love at all costs. How could any of this be associated with the bitter regretful hollow path Catherine and Heathcliff took? How could we forgive them for crushing their own reason for existence so brutally? How could the moors represent them if they abandoned the moors and betrayed themselves?

Heathcliff, while on the verge of insanity during Catherine’s last years on earth, is but insane after her death. His calm out pour of desperation to Nelly terrifies her of what desperate soul has got hold of Heathcliff. To Nelly’s shock, he recounts his visit to Catherine’s grave during the snowfall on the eve of her burial, and recollects his resolve to dig up the earth under which she lays, and open her coffin to slip next to her and be buried with her. It is his wild imagination that saves him moments from doing this unthinkable act: he hears a sigh that he knows to be Catherine and it is chilling to read his account of it thereafter:

“I felt Cathy was there: not under me, but on the earth. A sudden sense of relief flowed, from my heart through every limb. I relinquished my labour of agony and turned consoled at once: unspeakably consoled.”

To Heathcliff’s wildest disappointment, Catherine never shows. He paces day and night in search of her. He listens desperately to hear her sigh again. He is consumed by the thought of seeing her and being united with her. He waits for her to come back for 18 painful years, and while he suffers, he turns bitter. The desperation turns savage and dark. Cathy is gone and Heathcliff shall have revenge on the souls of two generations born of himself and of her and he shall wreak havoc and agony to the lives of his own blood. His sadistic acts towards his own son Linton whom he despises, little Catherine Linton, and especially Hareton, Hindley’s son, perhaps seem unforgivable and unjustified – but who are we to tell what Heathcliff suffered, and if we knew the true measure of that suffering, perhaps it is kindness he was exercising relative to his thirst for revenge. Perhaps, the cruelty might have been directed at him in seeing the worst characteristic traits in his own son Linton, while Hareton was endowed with all innate qualities of a fine man – and no amount of education and upbringing could save the former or lessen the latter. Heathcliff despises them both.

The strange courtship of little Miss Catherine and Linton is a match made in hell, and a match that Heathcliff forces upon them as part of his master plan. While little Catherine is dealt a poor card in this terrible game, she becomes immune to pain after her father’s death. She matures overnight, and handles the slow death of her husband Linton and the horrific treatments at the hand of Heathcliff, remarkably well. The more she reminds him of Cathy, the more Heathcliff despises her – and yet it is those same characteristics of defiance, perseverance, and survival that come to little Catherine’s rescue and keep her from falling apart.

After Heathcliff’s death, she and Hareton marry and manage to find a semblance of happiness within the dismal prospects of their lives. Nelly puts it best: “They are afraid of nothing. Together, they would brave Satan and all his legions”.

Oh How I Loved Wuthering Heights. After reading Emily Brontë’s singular novel, I moved on toJane Eyre by her sister Charlotte Brontë (which I subsequently loved), in hopes that if I read her sister’s writing, I may feel closer to her. If there ever was timeless fiction and timeless prose, it is embodied in Wuthering Heights and by Emily Brontë through and through.

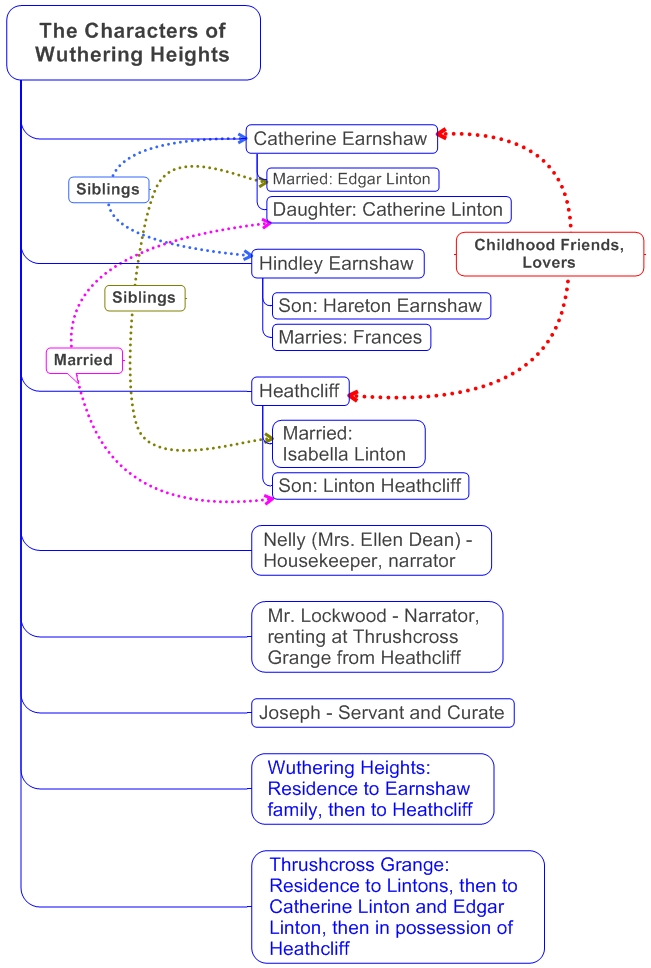

Image: Created using Mindjet MindManager application

I am Farnoosh, the founder of Prolific Living. So glad you are here. My mission is to empower you to unblock your creative genius to live your dream life.

I am Farnoosh, the founder of Prolific Living. So glad you are here. My mission is to empower you to unblock your creative genius to live your dream life.