I finally know the timeless story of Madame Bovary.

What a remarkable journey to delve into the timeless classics whose names I first heard uttered in adult conversations in my childhood in Iran. The Godfather is such an example. Victor Hugo’s Les Les Misérables another. Madame Bovary yet another.

What a remarkable journey to delve into the timeless classics whose names I first heard uttered in adult conversations in my childhood in Iran. The Godfather is such an example. Victor Hugo’s Les Les Misérables another. Madame Bovary yet another.

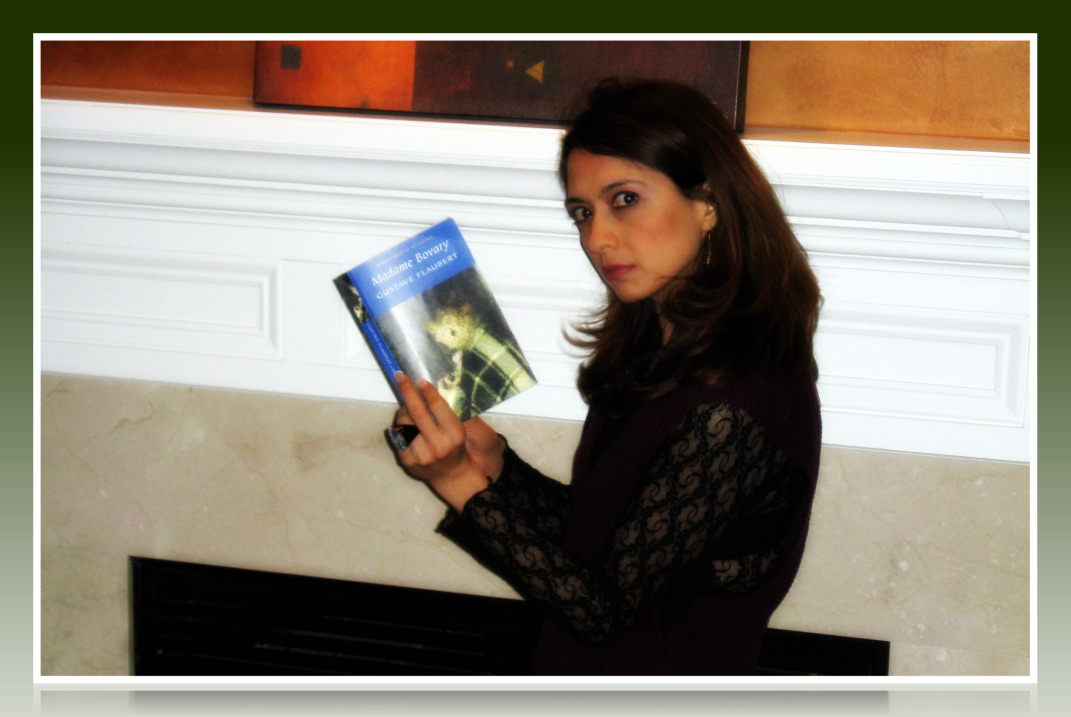

I read Gustave Flaubert‘s masterpiece in English, translated not by Penguin Classics which seems to be the most well-known version but by Wordsworth Classics, which I picked up in a small bookstore in London. Despite the extremely smooth translation with countless awe-inspiring passages, I have no doubt much was lost in translation from the prose and poetic style associated with the original French version.

The setting is France provincial life. The year is 1855.

Emma Bovary is the central character in Gustave Flaubert’s masterpiece which is written from third person point of view. She comes into the novel rather late. Flaubert first focuses on Charles Bovary’s grim childhood and adulthood, his studies to become a doctor, and his first marriage to the rich and dull Madame Bovary who dies quickly, leaving Charles to marry the young and dreamy Emma. The author certainly tries my patience as a reader before gluing me into Emma’s entangled and conflicted character.

It is disturbing to feel as such unease to articulate my thoughts about this world-renowned novel when it has stirred so many opinions and feelings. For 2 weeks straight, every morning before sunrise by the fireplace and every night before bed, I was glued to the pages of this book, half-disturbed, half-curious, and fully determined to see it through. Despite the initial struggle to acclimate my mind to the tone and voice of the novel, there is never a part of me that has regretted reading a classic and the gifted writing of Flaubert’s Madame Bovary certainly falls in that category.

For me, the only character of interest was Emma, followed only as it concerned her, by her lovers, Léon and Rudolphe and only by mild curiosity, her husband Charles. Why did Flaubert waste my time talking about the pharmacist Monsieur Homais, his dull wife, Madame Homais, his annoying family, the priest, the servants, the politicians, the world of agriculture and medicine and the other banalities of provincial life in Yonville? Naturally, it was to build the backdrop of a great story and necessary act to color Emma in all her true shades against this backdrop. But I only wanted to know Emma. I only wanted to concern myself about her every passing thought, emotion, whim, fancy, ache, pain, disgust and triumph. I wanted all of Madame Bovary — the novel — to be about this one single character, so complex and intense and fanatical she was that there was no tiring of her.

In a few words, I found Emma to be in painful conflict with the course of life, the people surrounding her, her fate of having this husband and this child, her apparent destiny, and her own self. She has been cast as an unlikable and unsympathetic character. That Flaubert was trying to portray her as one way or another is not the point at all. He was one of the first authors to cast an ordinary character from everyday life into a novel, a new movement in literature and one that brought him naturally much criticism especially in light of Emma’s adulterous and sacrilegious actions.

So I don’t think the question is whether we like Emma or whether we identify with her. The question is whether we can appreciate first the mastery of the prose and second the complexity and unique character of Emma Bovary. I applaud Flaubert’s remarkable candor and ability to precisely portray the unfulfilled desires, cravings, and yearnings of a selfish woman bound to a dull and kind husband for whom she shows no trace of emotion, and I do that without necessarily applauding Emma’s actions. In fact, to me, Emma hardly loved any of her lovers. I argue that she lived and breathed happiness only in the ideas of the circumstances, without loving anyone at all. She took pleasure in the fact that she was desired and loved by other men than Charles, and her feminine ways brought her men to their knees and made their survival without her nearly impossible. She felt fulfillment in this knowledge and found her self-worth through her lovers’ adoration and worship of her. By the same token, she felt loneliness, despair and anguish in the abandonment of such feelings.

Reading is the best pastime for an active mind! If you like to see the other book reviews, check the index of In Print.

There is so many more facets to Emma than her love affairs and her growing disgust with Charles and her growing detachment to her daughter, Berthe. There is her swaying from one extreme to another, searching for the same illusion of happiness in other places. At the onset of her marriage and the early disappointments of unfulfilled desires, she turns to fashion and furniture. After Rudolphe’s letter when she falls seriously ill for 43 days, she wakes up to a feverish desire to learn about Christianity and service and communion with a renewed sense of motherhood and superficial care for Charles. During her relations with Leon, she becomes kinder to Charles and turns to lavish spending and all the while, deceiving Charles by masterfully manipulating the financial trace of her actions. She swings between extremes in a path of illusions and fantasies, none of which brings her peace of mind or happiness for longer than a few hours or a few days. She might have found both peace and resignation in her last act of desperation when she swallows arsenic and dies a painful death.

Even in translation, the beauty of passages leaves you wanting more. Here are some, and only some as there were ever so many, of my most favorite parts, either in prose or in meaning, from the novel:

“Before marriage she thought herself in love; but the happiness that should have followed this love not having come, she must, she thought, have been mistaken. And Emma tried to find out what one meant exactly in life by the words felicity, passion, rapture, that has seemed to her so beautiful in books. “

-pg. 27, on first realizing the gap between her vision of marriage and the reality of it.

“He considered the judgment of the one infallible, and yet he thought the conduct of the other irreproachable”

-pg. 33, on Charles being torn, as he often was, between his mother’s judgment of Emma and the latter’s questionable actions.

“….the excitement of the theater, the brilliance of the balls, they were living lives where the heart had room to expand and the senses to develop.”

-pg. 36, on the life that Leon was leading in Paris with the imaginary friends and lovers that Emma imagined him to have.

“The hours slip by. Motionless we traverse countries we fancy we see, and your thought, blending with the fiction, playing with details, follows the outline of the adventures. It mingles with the characters, and it seems as if it were yourself palpitating beneath their costumes”

-pg. 63, Léon explaining the art of theater to Emma.

“How was it that she – she, who was so intelligent – could have allowed herself to be deceived again, and through what deplorable madness had she thus ruined her life by continual sacrifices? She recalled all her instincts of luxury, all the privations of her soul, the sordidness of marriage, of the household of her dream sinking the mire like wounded swallows; all that she had longed for, all that she had denied herself, all that she might have had! And for what? For what?“

-pg. 141, Emma reflecting on her deep long regrets at marriage.

“She gave herself up to the lullaby of the melodies, and felt all her being vibrate as if the violin bows were drawn over her nerves. She had not eyes enough to look at the costumes, the scenery, he actors, the painted trees that shook when anyone walked, and the velvet caps, cloaks, swords – all those imaginary things that floated amid the harmony as in the atmosphere of another world.”

-pg 170, Emma’s reaction to the theater.

“No matter! She was not happy – she never had been. Whence came this insufficiency in life – this instantaneous turning to decay of everything on which she leant? But if there were somewhere a being strong and beautiful, a valiant nature, full at once of exaltation and refinement, a poet’s heart in angel’s form,…. why, perchance, should she not find him? Ah! how impossible! Besides, noting was worth the trouble of seeking it; everything was a lie.”

-pg. 217, Emma’s self-reflections on the miseries of her life and attempts in vain at happiness

I loved Madame Bovary. I do not know whether I loved Emma for who she was and all of her complexity and desires and selfish conquests, or for how Flaubert portrayed her in irresistibly beautiful poetic prose but there is no mistake about it: Madame Bovary is one of the greatest novels of all time. It was published only 20 years before Leo Tolstoy‘s Anna Karenina, a similarly conflicted yet magnificent character as Flaubert’s Emma. In both of these novels, we are introduced to unforgettable female characters in literature, who mesmerize us with their conflict, complexity, range of desires and emotions, and search for meaning and happiness in similarly doomed paths. Oddly enough, I read a modern day version of Tolstoy’s masterpiece, a remarkably well-written novel by Irina Reyn titled “What happened to Anna K.?” two years ago, and tomorrow, I am starting the original Tolstoy novel.

I am Farnoosh, the founder of Prolific Living. So glad you are here. My mission is to empower you to unblock your creative genius to live your dream life.

I am Farnoosh, the founder of Prolific Living. So glad you are here. My mission is to empower you to unblock your creative genius to live your dream life.