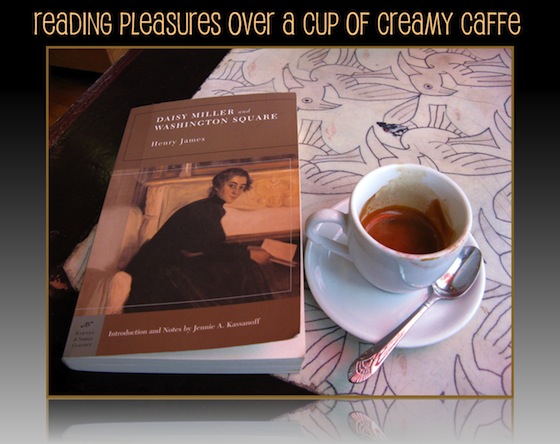

I read “Daisy Miller” and “Washington Square” because Azar Nafisi mentioned them in “Reading Lolita in Tehran“. I had set out to complete the reading list of all the books mentioned in Nafisi’s tales of Iran, and next on my list were these two short novels of Henry James. They came in the same book. I read “Daisy Miller” first, and while it’s a tiny 62 pages, it took me weeks to get past the first few alone. I remember starting out the same way with “Jane Eyre” and fell in love with her gradually. So I stuck it out. I remember hearing about Eleanor Roosevelt’s theory that motivation will come to you if you are already working, so put yourself in autopilot of the task at hand at first, go through the motions, and motivation will come to you then but not any sooner.

You do not have to fully understand a classic to appreciate it on a small or grand scale. Often, before I read a book, I set expectations based on previous reviews or references to the story, and I silently aspire to meet them. Expectations that the book will inspire me in one way or make me laugh and teach me a lesson in another. Well, expectations usually lead to failures, so I need a new strategy. Now I am reading my classics with no preconceived notions or demands on the author or the book, and that is the paradigm shift with which I read and now write about the 2 novels of Henry James.

Daisy Miller: Daisy Miller disappointed on the plot and character, but it surpassed on the writing style and story telling. My first impressions were indeed reflective of my very last ones. Taking place in the beautiful Switzerland and Italy, between two Americans who meet abroad: the beautiful Daisy Miller and the reserved and refined Winterbourne who wishes to court her, it is a story less on courtship and romance and more on the personality eccentricities of Daisy Miller. Much as I tried, I was not taken by Daisy’s lackadaisical character. In fact, I took a great dislike to her, and could not produce any sympathy for the misfortunes that later befall her. In general I consider selfishness a virtue, so my opinion must have come from the indifferent, irresponsible, immature characteristic traits that produced so little to like about Daisy. She is flirtatious, fun-loving, whimsical and careless. She plays tricks and games of emotion with Winterbourne, and she pays the ultimate price with her games.

Even so, I bestow the usual resentment and disgust towards the judgmental, low-class, middle-aged women of the earlier generation who consider it their business to decide wrong or right where Daisy’s personal life and decisions are concerned. To all of this, Daisy reacts with tact and responses that are well-thought-out, calmly expressed, and firmly put. One of my favorites is this one when Winterbourne asks her concerns if she cares to know what people say about her carefree runarounds with the Italian men in town: “Of course I care to know. But I don’t believe it. They are only pretending to be shocked. They don’t care a straw what I do….” and she is ready to dismiss it and move on.

The byproduct of reading Daisy Miller is that it served me as a warm-up to Henry James’s writing style. It also reminded me on several occasions to that of one of my beloved authors, Jane Austen, a writing style with poetic harmony where mere words flow into phrases and dialogues into memorable conversations, the command of the English language at an admirably accomplished level, and the question of ethics and morality being one of the highest measures of a good character. Yet James has his own voice, his own twist of words and phrases, his own manner of telling the story. You can tell he is an American writer. So I must say that for Daisy Miller, the writing is superb, poetic and harmonic, almost like music. There are several passages between Winterbourne and Daisy Miller that I enjoyed thoroughly, and I learned from reading Daisy Miller, and setting aside expectations, that you can take away your own golden nugget from reading a classic, but hardly will you walk away with regret.

Washington Square: Strangely addictive and impossible to put down, this novel grows on you like persistent ivy, takes you down the path of a deliciously and slowly narrated story, and in the end leaves you completely dissatisfied, puzzled, and aggravated that the anticipated sweet spot never comes, much like poor sex. You bet I was outraged, and yet content to have read it nonetheless. I had no idea about the plot beforehand. The novel is written from the perspective of a third-person observer who years later recounts the story that happened at Washington Square in NY. I liked the setting and the story teller’s voice.

We are first introduced to Dr. Sloper, the calculating, mathematically exact, stoic, brilliant medical doctor with a outstanding reputation for saving lives and curing illnesses over his long career. The later years are not kind to him and the ultimate irony befalls him when he is unable to save his own small baby boy from a disease as well as his wife during the second childbirth. His son he adored for being a son, naturally, and his wife he worshiped for her intelligence, elegance, beauty and for understanding him. He is left with a daughter, Catherine, and brilliant as our doctor may be, he considers females to be of the lesser sex – and dear Catherine starts out very poorly with causing the death of her own mother, however helplessly that it may have been.

To ease the burden of having to care for Catherine, he invites his widowed sister, Mrs. Penniman to live with them. She personifies the usual meddlesome, annoying, know-it-all older woman who takes pure pleasure in creating unnecessary drama and inevitable anguish in the lives of younger people, quite similar to Mrs. Jenninges in Pride and Prejudice, but with lesser intent for good. As the years pass, Catherine grows up to be quiet and shy, awkward and lonesome, reserved and obedient, without much opinion or expression on anything but most of all, in constant want of fatherly love and approval. Dr. Sloper’s words, mixed sparingly with compassion and kindness, usually cut like a blade and leave you wishing he had not said anything at all instead. He makes derogatory remarks about his daughter, whom he finds far from intelligent, charming or beautiful, in public and to her face. One reviewer wrote that she had to perform “linguistic surgery” to piece together the rare morsels of kindness from the doctor’s speeches. In these passages, while I was enjoying the reading just fine, I was by no means terribly interested in either the plot or the outcome. Not just yet.

The inevitable happens. Catherine meets a suitor. The young, beautiful Mr. Morris Townsend who is back in NY from his recent adventures, one day sits next to shy Catherine Sloper at a party and and hears himself talk for over an hour. Catherine is subdued, and yet to her impressionable eyes, he seems to fit into a picture of happiness. She soon morphs him into the ideal man for her, and some sort of courting ensues. Mr. Townsend as he is hereafter referred to except Morris on occasion by Catherine, comes to the house frequently to visit. During this time, the Doctor’s curiosity is naturally raised and he asks Mrs. Penniman on the account of Mr. Townsend, and later of his other sister, the only sibling whose opinion he seeks and respects, Mrs. Almond. After gathering his facts about Mr. Townsend, little that they may be, he decides once and for all, that the suitor is after Catherine’s inheritance, both from her mother’s side and from what her father will leave her. He refuses to bless the couple. Catherine refuses to give up on his father, and this is exactly where my interest is piqued. I must admit that on the whole, I found the father to be stern but likely looking out for Catherine’s best interest, and I hardly cared for Mr. Townsend but those are small stuff in the face of what really interested me.

Reading is the best pastime for an active mind! If you like to see the other book reviews, check the index of In Print.

You see, the story is ordinary and realistic, the situation is a very typical difference of opinion between daughter and father with dynamics of a meddlesome third-party. It is the quiet and reserved Catherine’s expression, in the stern, adamant way with which the doctor rejects the suitor, the persistence of Catherine to let him give her lover a chance, the mysteriously restrained and calm manner which she affords the situation that would ultimately determine her fate – it is these aspects of the story that made me a faithful reader to the last page. Catherine leads the most logical and practical course of action in her unresolved and impossible dilemma, and she handles the agony of anticipation for months and years as she waits patiently and makes us wait along with her. It is these components that infused with the spellbinding writing style of Henry James, render this book a page turner beyond belief. For Catherine’s character belongs to no category, and can only be experienced through the reading of her story.

Catherine has been dealt an unfair shake of the deck, and her father and aunt, in their own special ways, abuse her eternal goodness and her intent to do right by them. In Reading Lolita in Tehran, Nafisi refers to how they removed the layers of goodness one by one from Catherine. At one point, she simply said to her aunt, “I don’t care anymore to please him.” And ironically, soon after, she faces the ultimate dismissal from Morris who breaks the engagement. This marks the only occasion on which she gives into her grief, and the only one where, albeit briefly, we observe some outlet of emotion from the strained child. Perhaps, she loses some layers of goodness or intent to do goodness. I did not see it that strongly. To me, Catherine remains as much of a saint throughout this ordeal as it is humanely possible.

Yet even when we know the answer to the ultimate hanging question – will she marry him? will she give him up? – on the day that Morris leaves her, the story seems to me rather anticlimactic, perhaps for two reasons: Catherine shows very little emotion and it is not what we expect a climax to bring about for the main character, and second, the story keeps going. The narrator takes us to the future. The years pass. She is past 30 and then past 40 years of age, and living to become an old maid who never married. Why does James take us along this path and not just tell us what happened to her, because as Catherine said, “The years have passed very quietly.” As a reader, it felt strange to be reading about these quiet years. Maybe this is the realism aspect of Henry James writing. Real life has a lot of quiet moments, and for Catherine, one too many perhaps.

The burning question for me was why she refused to make the promise to the doctor to never marry Morris after his death. “I can’t promise that, and I can’t explain“, Catherine says. She makes the doctor very angry and costs herself a rather large portion of what would have been in his will for her. This leaves us thinking that she has ulterior motives, that she has plans, hopes, dreams to pursue when he is gone. And yet the author awards us with neither an explanation nor a motive for why Catherine said those words. Did she want to keep a sense of freedom, when it was impossible to lose anything else after her permanent wound? Perhaps. Did she wish to hurt her father in return by not giving him the satisfaction he was asking for? Doubtful from what we know of her personality – she never showed any tendencies towards malice or vengeance. Perhaps then, she wanted to leave the door open and Morris just came very late. I am still not sold on that. Who knows besides Henry James? No one. Perhaps, there is a time in life when we stop pursuing a dream of our youth, a point of no return to the past when too much time has passed, a nonchalance to even our own chance for happiness when we are so used to lack of it and it takes so much courage to take a risk again.

The agonizing story of Catherine Sloper will ring in my ears forever. I forgive the author for straying me without delivering what I fully expected as the reader. I shall let my imagination decide the reasons which prompted the lovelorn and heart broken Catherine to choose the path of her life and her disposition in general.

I am very grateful nonetheless. It is thanks to learning to delay quick judgment and possible dismissal of what turned out to be a truly unique story and writing voice, that I now count among my favorite authors, Henry James.

I am Farnoosh, the founder of Prolific Living. So glad you are here. My mission is to empower you to unblock your creative genius to live your dream life.

I am Farnoosh, the founder of Prolific Living. So glad you are here. My mission is to empower you to unblock your creative genius to live your dream life.