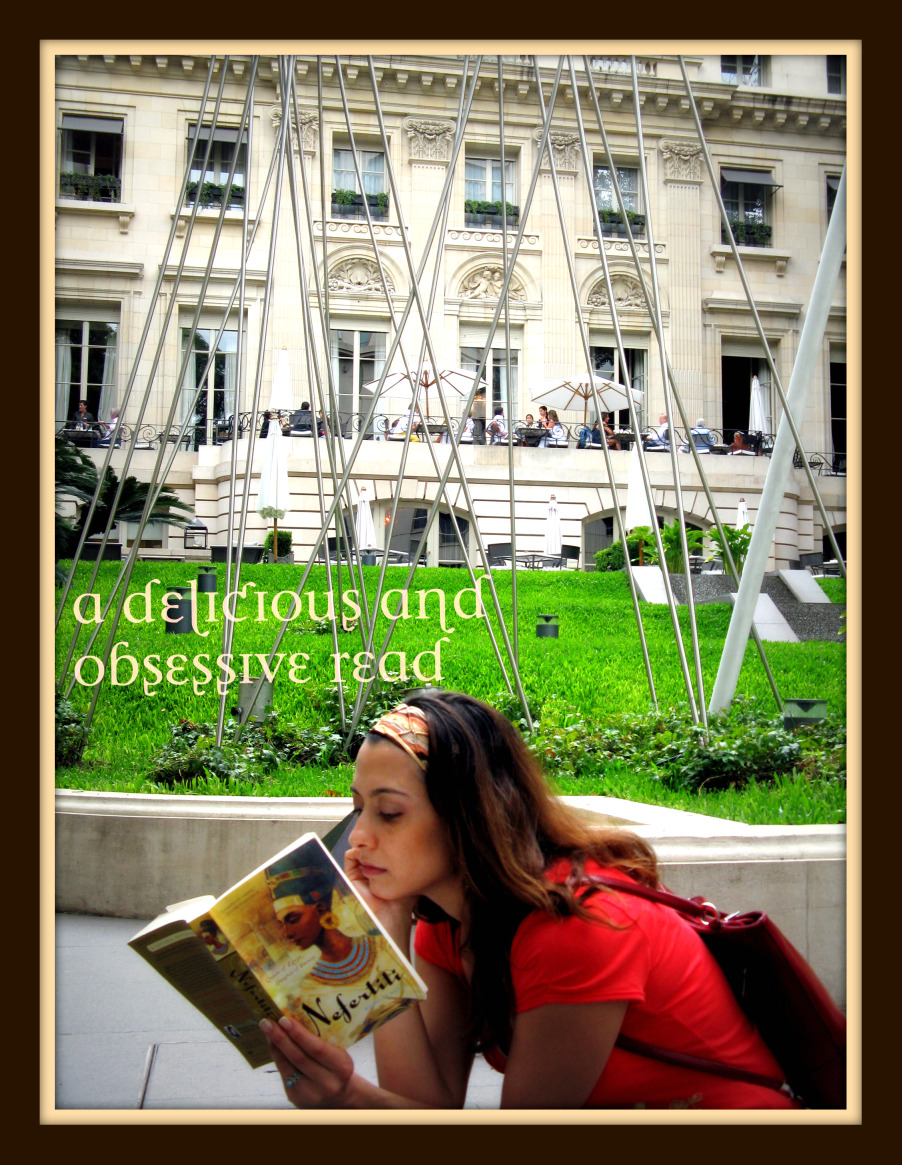

The most magnificent films of our time would be hard pressed in creating the visual images Michelle Moran stirs up with her powerful words, from a history that existed over three thousand years ago, a kingdom that ruled in the heart of Egypt in an unstable period, and a queen that was so beautiful and graceful that eternity indeed remembers her, as she had desperately hoped it would. “Nefertiti” is compulsively readable and a treasure of historical fiction to behold. When I picked Cleopatra’s Daughter from my Amazon vine program, I was mesmerized by Moran’s prose and deep knowledge of the period about which she writes. She equally if not better matches it with her exceptional ability to arouse our curiosity, pique our interest, foster our sympathy and feed our thirst and ache to know the outcome. Her writing skills are so keen and polished you cannot help but devour the insanely obsessive page-turner that is Nefertiti.

The most magnificent films of our time would be hard pressed in creating the visual images Michelle Moran stirs up with her powerful words, from a history that existed over three thousand years ago, a kingdom that ruled in the heart of Egypt in an unstable period, and a queen that was so beautiful and graceful that eternity indeed remembers her, as she had desperately hoped it would. “Nefertiti” is compulsively readable and a treasure of historical fiction to behold. When I picked Cleopatra’s Daughter from my Amazon vine program, I was mesmerized by Moran’s prose and deep knowledge of the period about which she writes. She equally if not better matches it with her exceptional ability to arouse our curiosity, pique our interest, foster our sympathy and feed our thirst and ache to know the outcome. Her writing skills are so keen and polished you cannot help but devour the insanely obsessive page-turner that is Nefertiti.

First, a mini crash-course that I certainly would have appreciated on ancient Egyptian Gods and beliefs most mentioned in the novel:

Aten: A sun disk worshipped as the new God during the reign of Akhenaten

Amun: The most important Egyptian God and the creator of all things

Anubis: Guardian of the dead, believed to have weighed the deceased’s heart on the scales of justice to see if they can pass to the Blessed Lands

Isis: The Goddess of beauty and magic

Ma’at: The Ancient Egyptian concept of truth, balance, order, law, morality, and justice

Osiris: Husband of Isis and judge of the dead, symbol of eternal life

Pharaoh: Title of absolute ruler of ancient Egypt dynasty both in political and religious aspect

Ramesses: Born of sun-god Ra, name conventionally given to 11 Egyptian pharaohs

Tawarat: Goddess of fertility and childbirth, it is in the shape of a hippopotamus

Vizier: Adviser to the royal family and particularly to the Pharaoh

Thebes, Egypt. 1351 BC. “If you are to believe what the viziers say, then Amunhotep killed his brother for the crown of Egypt.” And so starts the greatest novel about Egypt’s most alluring and powerful Queen Nefertiti and its most unstable, self-centered and ignorant Pharaoh Amunhotep, told through the narrative voice of her younger sister, Mutnodjmet (Mutny).

Nefertiti is 15 years old and about to be wed to Prince Amunhotep who is soon to be Pharaoh of Egypt. Together, they make a miscalculated move away from the Gods of ancient Egypt and the High Priests and pay dearly for the price of their blind ambition and dangerous games. In this superbly written novel, history unfolds around Nefertiti’s blind and magnificent reign as Queen and later as Pharaoh while Mutny is witness to growing political and religious forces building against her sister. The tale of two sisters could not be more enthralling with Mutny feeling bound to Nefertiti, despite her arrogance, her selfishness, her blind decisions and her cruelty. Irony and fate make for an unexpected outcome for the royal sisters and much like life, the patient one with common sense perseveres.

When Mutny is trying to dissuade her sister from killing the unborn child of Kiya, the 1st wife of Amunhotep, she rebukes flatly, “Power is cruel. It will either be hers or mine.” Nefertiti’s simple statements convey a thousand words about the thoughts and values of this queen. For all her unmatched beauty and grace, she nurses cruel ambitions. She embodies every classical tale of doomed success by thinking her Goddess-like beauty invincible, her actions forgivable and her cruelty and cunning overlooked when Anubis knocks on her palace doors one day.

For me, it is impossible to like Nefertiti, to understand her cause and to sympathize with her incredible losses in the end. But it is entirely possible to be in complete awe of a queen with unmatched ambition, sharp cunning, and supreme influence over her Pharaoh. She establishes the “first” of many things – why can the bell not toll three times when a Princess is born the way it does for a Prince? Why can a Princess not ride a chariot or horses the way a Prince does? Why can a Queen not lead all of Egypt the way a Pharaoh does? Why can a Queen not bed the Pharaoh in his own chamber? She broke every boundary of Egypt’s history and walked across every threshold no Queen had dared to step before. For that audacious trait of her personality I commend her and think her a supreme example of success. By asking a question and imagining everything possible, especially if it has never been done before.

Is a mindset of achieving supremacy at any price and at any risk born or bred? The Pharaoh of Egypt is just as much a cunning match to his wife in this game of power and ambition gone wild. Nefertiti and Amunhotep destroy belief systems held tightly by generations of Egyptians, strip the High priests from their power and deities and rewrite their own version of history on the pillars of Egypt. Amunhotep abandons not only the Gods of Egypt but also the capital from Thebes to the desert city of Amarna. He establishes the worship of Aten during his 17-year reign and builds countless temples and palaces in the dessert sands of Amarna. He changes his own name to Akhenaten and bans the worship of any other Gods in the city. He is rash and impulsive, irrational and brazen, and horribly unstable. He betrays his war General and thinks himself immune to even the plague. In every ridiculous decision, Nefertiti stands by him like an unconditional loyal partner. He builds and destroys a kingdom with his own foolish pride and dies a painful lonely death locked up in his palace chamber in the company of the Black Death that deservedly and at long last finishes him. Egyptian people take a well-deserved revenge on his soul, his buildings and temples, robbing all future generations of the sweat of those Egyptian soldiers forced to build phenomenal temples and statues, soldiers who would rather have been fighting the Hitties from taking their land – But Akhenaten was far too focused on building a kingdom to protect one.

Reading is the best pastime for an active mind! If you like to see the other book reviews, check the index of In Print.

The wildly unstable and blindly ambitious Pharaoh ignores the counsel of the highest advisers and goes against every common sense approach to attain that which he wants – Building a kingdom in the dessert worshiping a new God while all of Egypt worships him and his God. When Vizier Ay, Nefertiti’s father and Akhenaten’s closest counsel, announces to the Pharaoh that the plague has swept through his beloved Amarna by the enemies he himself invited to boast of the pillars erected in his honor, his response is both funny and shocking. “Impossible” he retorts. “We scarified two hundred bulls to Aten!”

In that one phrase, he renders all the ignorance and darkness of his self-appointed beliefs. His thoughts are racing fast and furious: he did his part of the bargain so why did Aten retaliate? While the Pharaoh acts as a lunatic to me, thinking himself above the Black Death and all earthly tragedies, with his negotiations and the expectations on outcomes of events, he is a Heretic to his people who believe much similar things through worship of their own deities in stone, sand, sun and animals. Altogether, the ancient Egyptians seem logical, calculated, scientific, brilliant builders and scholars on the one hand, and devout believers of their countless Gods, the ways of universe and the afterlife on the other hand.

Michelle Moran writes beautifully. She is gifted as a historian. Her dialogues are passionate, subtle, deep, and memorable. Her characters well-developed and perfectly etched in your memory long after you finish reading her books. Her sense of humor is subtle and her knowledge of the subject matter is simply commendable. I cannot wait to start the Heretic Queen, the sequel to Nefertiti.

Until reading Cleopatra’s Daughter, I did not have the remotest idea about my thirst of knowledge to learn the history of civilizations and kingdoms which came thousands of years before me. To imagine what the earth and the world resembled three thousand years ago is mind boggling. It makes me wonder if the length of time is the only factor that makes it seem so fascinating – perhaps, but not entirely. My fascination is multi-fold. It is in the superb advancements and repository of knowledge of the ancient Egyptians and their way of life which were later lost for future generations, with only some re-discovered. It is in the mystique of treasures that are perhaps destroyed forever. It is in the trace of what remains in our museums that speaks so grandly of the magnificent things we were not fortunate enough to inherit at the hands of time.

I am Farnoosh, the founder of Prolific Living. So glad you are here. My mission is to empower you to unblock your creative genius to live your dream life.

I am Farnoosh, the founder of Prolific Living. So glad you are here. My mission is to empower you to unblock your creative genius to live your dream life.