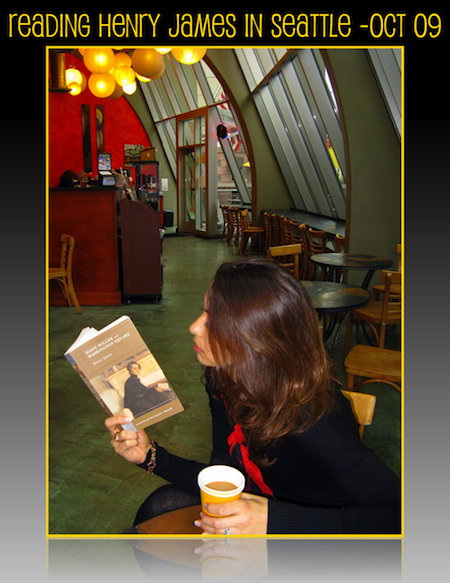

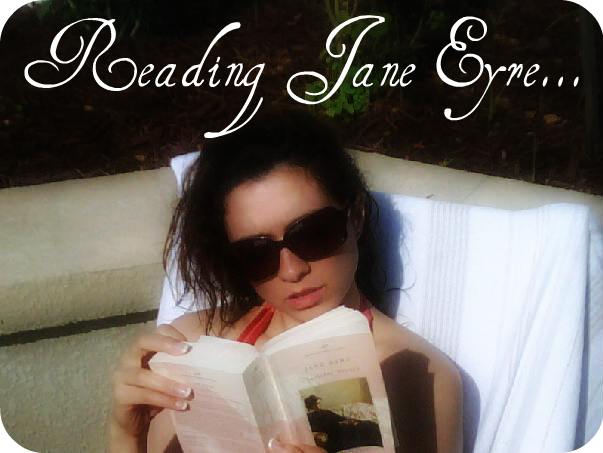

I read “Daisy Miller” and “Washington Square” because Azar Nafisi mentioned them in “Reading Lolita in Tehran“. I had set out to complete the reading list of all the books mentioned in Nafisi’s tales of Iran, and next on my list were these two short novels of Henry James. They came in the same book. I read “Daisy Miller” first, and while it’s a tiny 62 pages, it took me weeks to get past the first few alone. I remember starting out the same way with “Jane Eyre” and fell in love with her gradually. So I stuck it out. I remember hearing about Eleanor Roosevelt’s theory that motivation will come to you if you are already working, so put yourself in autopilot of the task at hand at first, go through the motions, and motivation will come to you then but not any sooner. [Read more…] about Henry James: “Daisy Miller” and “Washington Square”

I am Farnoosh, the founder of Prolific Living. So glad you are here. My mission is to empower you to unblock your creative genius to live your dream life.

I am Farnoosh, the founder of Prolific Living. So glad you are here. My mission is to empower you to unblock your creative genius to live your dream life.