Opening paragraph of Yoko Ogawa‘s short story:

“What is your shoe size?”

“How much did you weigh when you were born?”

“What is your height?”

“When is your birthday?”

These were some of the questions the housekeeper encountered every morning from the professor whom she cared for. He asked because he loved mathematics and because he could not remember her. They were introduced anew every morning. The answers to these questions, all of which she happily returned every single time, comforted the professor as he delved back into his math world, and delivered a most accurate relationship between seemingly random numbers.

The professor loved two things deeply: mathematics and children. Mathematics was one of two things accessible to him as he had no children; this makes the story particularly sweet as the housekeeper is urged to bring his son over to the cottage because the professor is paranoid about mothers ever leaving their children’s sight.

The mathematics that Ogawa gives us in this novel are simply beautiful — she is not alluding to math in the context of her story, she is teaching us, through fun and games, subtle yet profound relationships between numbers. What do 220 and 284 have in common? Both are even and both are 3-digits. Yet they are linked to one another through some divine scheme, a scheme so rare that Fermat and Descartes, both famous mathematicians, only found one such pair each.

The sum of factors of 220 add up to 284 and the reverse is true for 284. This makes them amicable numbers.

220: 1+2+4+5+10+11+20+22+44+55+110=284

&

284: 142+71+4+2+1=220

What is so special about the number 28? I loved being 28. It was naturally more special than 27 yet no less special than 29 but it only lasted until I turned 30 — so really, it was all relative at the time, not permanent like the property of the number 28 — and that property is this: The sum of factors of 28 add up to 28, making it a perfect number.

28: 1+2+4+7+14 =28

It is through mathematics and the devotion of the professor to her son, nicknamed Root for having a flat head like the square root sign, that the housekeeper grows attached and cares deeply about the professor. Just as the housekeeper observed, there is something peaceful and pure about numbers having relationships, perfectly logical and beautifully expressed relationships. There is something even more comforting to have the professor call out these relationships, as a matter of factly, and bind it to personal aspects of life — a shoe size, a refrigerator’s serial number, the weight of a child, the age of a woman, the birthday of a boy. It made the housekeeper feel special. It would have made me feel special too.

The professor is a genius — and as is true with all genius people, he has some outlandish skills that he finds useless and the rest of the world finds remarkable, with no practical application nonetheless, just as he agrees. He can repeat conversations and phrases in reverse. He can think up prime numbers up to the billions. He can pick out the first evening star in the afternoon sky. We may think having these skills would be terribly special, but in truth, I think it is more likely to bitterly isolate those who have them and are set so far apart from the rest of society.

While mathematics plays a large part in the story, baseball also plays a key role, much to my dismay. I do not like sports in general, much less reading about them, and in particular, my strongest dislikes are basketball and baseball. It is natural that Root loves baseball, he is a Japanese boy! It is a nice coincidence that the professor loved it too, as the baseball scores have a close relationship to mathematics, particularly to probabilities of success or failure. So while the professor and Root loved baseball for different reasons, they shared this passion. To Ogawa’s credit, for someone with such dislike for baseball, she did well to weave it into the story where it related, and I am pleased to have learned not so much about baseball as about the relationship of numbers to the game.

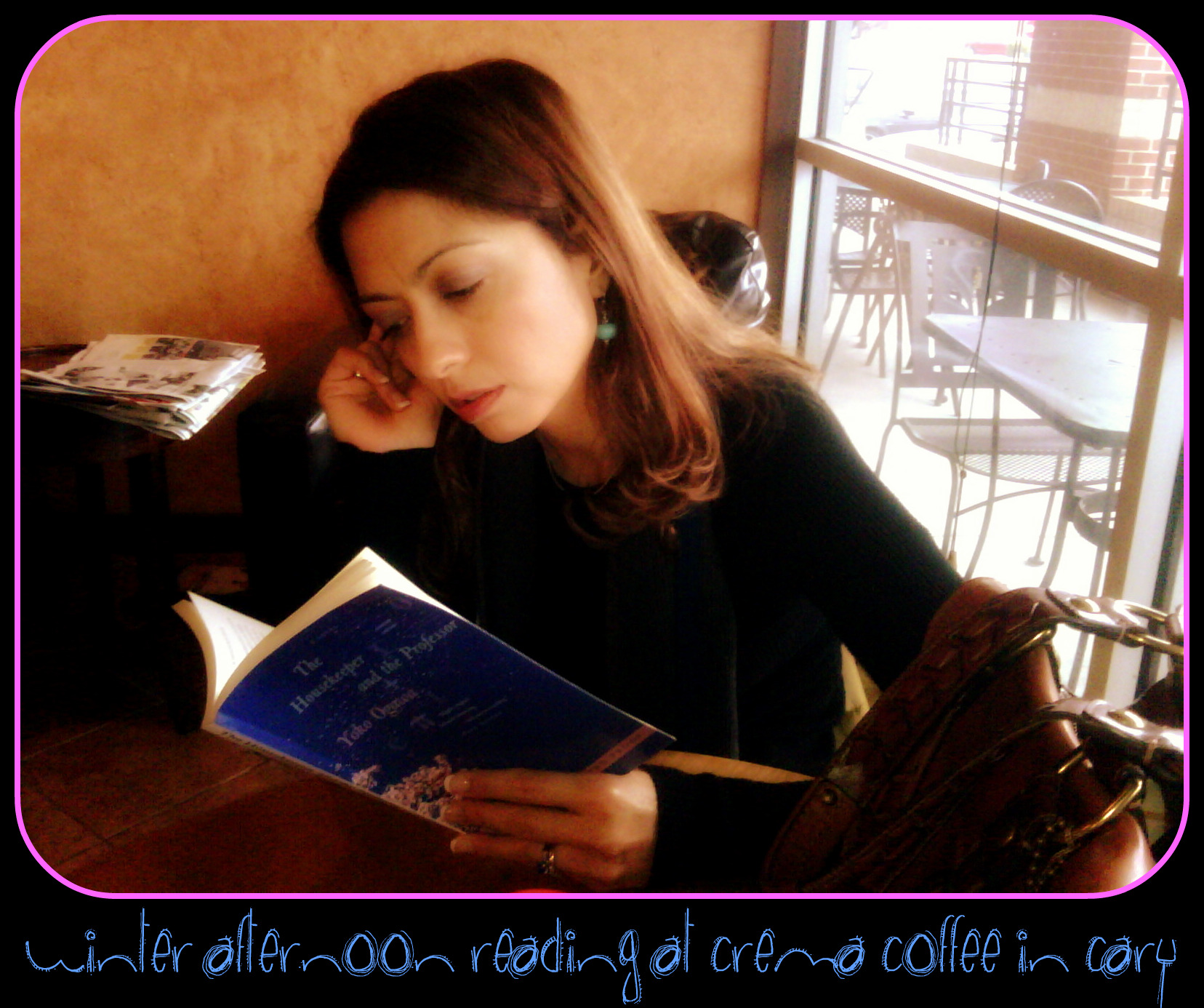

Reading is the best pastime for an active mind! If you like to see the other book reviews, check the index of In Print.

The memory of the professor lasts only 80 minutes. I had anticipated this to play a much larger part in the story. While it reappeared in and out of shadows, it made a poignant point when the housekeeper is temporarily let go and replaced by another. As she reminisces her time with the professor and their shared math secrets and moments of victory for the Tigers baseball team on the radio, she realizes that the professor at that instant has no recollection of any such memories in his short term memory and therefore no remorse, regret or pain associated with her departure.

If we had to do without it, what would we give up — the short term memory or the long term one? Would you want to part with your childhood memories or with memories of last summer’s vacation and yesterday’s dinner with friends? What are we without our memories? When my grandfathers passed away, within a year of each other, I often tried to keep their memory alive — their voice is the first thing that faded, and yet I know I would know it if I heard it again, the familiarity of it is deep in my memories, never to be erased.

One of my favorite passages is when the professor talks about his passion for mathematics: “The mathematical order is beautiful precisely because it has no effect on the real world. Life isn’t going to be easier, nor is anyone going to make a fortune, just because they know something about prime numbers…..The only goal is to discover the truth”. After solving a particularly difficult math problem, the professor tells the housekeeper that all math secrets are in God’s notebooks, and he only peeked to see what he needed to solve his minuscule problems at one time or another.

The story of the Housekeeper and the Professor is bittersweet. It shows us math in a new light, and relates it to us and us to it, and it proves that friendships can be renewed every day and still be strong and intact to the end, and that caring deeply for children can be an effort well-vested, especially the children who are poor in fortune.

Well-done Yoko Ogawa with clean, flowing writing style, and an easy story-telling format, interjected with the poignancy that is delivered well. “The Housekeeper and the Professor” is indeed a story to remember.

I am Farnoosh, the founder of Prolific Living. So glad you are here. My mission is to empower you to unblock your creative genius to live your dream life.

I am Farnoosh, the founder of Prolific Living. So glad you are here. My mission is to empower you to unblock your creative genius to live your dream life.